After Tony Lema fell in love with Betty Cline in 1962 he went on a hot streak finally breaking through for his first official PGA Tour event in Orange County. That victory, along with his stellar play that fall qualified him for his first Masters Tournament in 1963. He damn near won it. The following is excerpted from the new biography of Tony Lema titled Uncorked, The Life and Times of Champagne Tony Lema. You can order on Amazon HERE.

Updated 4/10/2020

Tony managed to secure pars on the fourteenth through seventeenth holes to remain at even par. Nicklaus added a birdie on the par 3 sixteenth to his birdie on the thirteenth to go two shots in front of Tony. Boros was unable to secure the birdie down the stretch he needed to catch Nicklaus. Tony knew his only chance to pull off the upset victory was to birdie the last hole and hope that Nicklaus would bogey either seventeen or eighteen.

The eighteenth hole is a difficult hole to birdie. The tee shot, from out of a chute of pine trees, demands a precisely placed shot on the dogleg right hole that plays uphill the entire way. Bunkers on the right protect the narrow green while a drop off on the left results in a very difficult chip shot. Two ridges divide the green into three distinct plateaus and makes putting very difficult.

Although Tony was tense, it was a good kind of tension. It focused his mind. He hit a good tee shot that left an approach shot to a pin located on the middle plateau of the green, slightly favoring the right side of the green. Tony knew if he landed the ball just off the green on the right side it would bounce towards the pin, but this also meant flirting with the bunker. He settled into the shot with positive thoughts. He hit a firm four-iron that hit his target and bounced up, and onto, the green, 22-feet above the hole.

Alfred Wright, in Sports Illustrated, wrote that Tony “looked over this scary putt with a poise that denied the torment inside him. For all one could tell, he might have been playing a $2 Nassau on Wednesday afternoon back home in San Leandro.”

He took off his glove as he and his caddy, Pokey (most Augusta caddies had colorful nicknames), looked over the putt. He tossed away his cigarette and got over the putt they read to break two ways. First, the putt would break to the right before curling back to the left closer to the cup. In addition, it was a slick putt, downhill all the way.

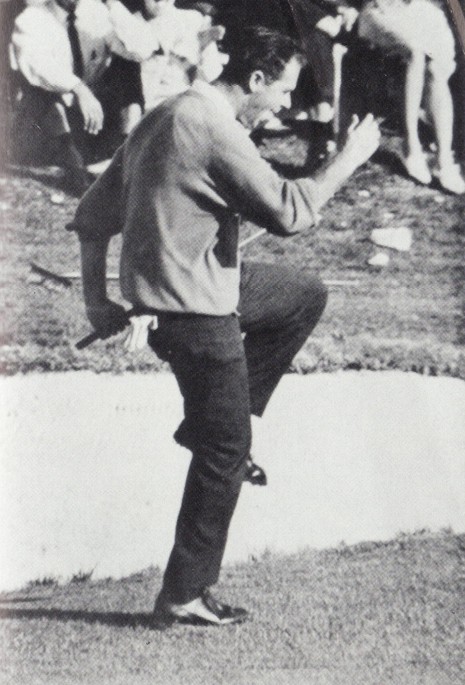

When he hit the putt, he knew it was good. He watched as it started on line and, as he thought it would, the ball started to break right. It held that line for an instant before it gradually swung back to the left and headed straight towards the hole. As the ball turned towards the hole, Tony began to chase it, moving to his left. When it disappeared into the hole, it was as if an explosion went off inside him. He roared in approval as he jumped into a little jig. The crowd around the final green erupted with one of the famous Augusta roars heard around the course.

A picture of Tony, by James Drake, shows Tony giving a fist pump with his right hand while he raised his left leg in the first step of his celebratory dance. Drake’s camera caught Tony with his mouth wide open releasing an ecstatic yell.

Before playing the seventeenth, he glanced at a leader board and discovered that only one player left on the course had a chance to beat him—Tony.

Nicklaus heard the huge roar that erupted from the eighteenth green. He delayed his second shot on the seventeenth hole until he could learn the reason. Before playing the seventeenth, he glanced at a leader board and discovered that only one player left on the course had a chance to beat him—Tony.

The leader board near the seventeenth green soon registered Tony’s birdie, so Nicklaus now knew he needed pars on both seventeen and eighteen to win. He managed a par on the seventeenth hole and headed for the tee at eighteen.

After his round, Tony felt wrung out and excited at the same time. He signed his card before officials escorted him to Cliff Roberts’s private office in the clubhouse. This was the same room where Venturi had watched on television as Palmer had birdied the last two holes in 1960 to defeat him. The same room where Gary Player had watched Palmer double bogey the eighteenth hole to hand him the green jacket in 1961.

In the room were Roberts and Bobby Jones, who Tony was meeting for the first time. Also in the room were Arnold Palmer, who as defending champion would participate in the green jacket ceremony, and Labron Harris who was low amateur for the event. There was a television set in the room providing tournament coverage as well as a television camera to record reactions in the room.

Palmer was glum and downhearted about his play in the tournament. Still, he heartily congratulated Tony on his fine play, as did the other men in the room. Servers poured drinks while everybody sat down to watch Nicklaus play the eighteenth hole.

“I didn’t try to play conservative golf at any time,” Nicklaus later explained, “but neither was I about to get reckless on the eighteenth.”

He hit his drive down the left, the safer side, of the fairway, where it ended up in a muddy patch. After a free drop to a drier spot on the fairway, he looked towards the green that appeared very small to him. From that side of the fairway he could only see the top half of the pin, the huge gallery and the gaping bunkers.

Nicklaus mapped out courses with precise yardages from landmarks, one of the few pros who did so at the time. He paced off the distance to his yardage marker, the last tree on the right, and calculated that he had 160-yards to the pin. The distance called for a normal six-iron for him. His approach left him a 35-foot putt from above the hole.

Watching the television, Tony knew how difficult Nicklaus’s downhill putt would be. He thought it was quite possible that Nicklaus could three-putt.

Watching the television, Tony knew how difficult Nicklaus’s downhill putt would be. He thought it was quite possible that Nicklaus could three-putt. Nicklaus took his customary lengthy time studying the putt before he stood over the ball. After a long pause, he at last struck the putt. He thought he hit a very good putt, thinking it was going in the hole. Instead, the putt ran three-feet past the hole.

Nicklaus again deliberated for a lengthy time studying the short, difficult putt. He stood, as if frozen, over the putt forever before he finally stroked the ball. When Tony saw his second putt, he did not think it had a chance to go in. Somehow, the ball held its line, climbed the hill and finally dove into the hole.

After his putt went in, Nicklaus took off his white ball cap and flung it towards the front of the green. He turned back towards the television camera with a huge smile on his face as his father, Charlie, ran onto the green and gave his son a big bear hug.

“I was kind of surprised when my first putt didn’t go in,” Nicklaus admitted after the round, “and I was even more surprised when my second one did.”

When the putt dropped, Tony felt as if every bit of emotion drained from him. He felt as if he would never be able to muster up the effort to get out of the chair he was sitting in. He felt deflated, almost numb.

Nicklaus signed his scorecard and then, on cloud nine, arrived at Robert’s office. All present in the room congratulated him before preparing to move to the presentation ceremonies held on the practice putting green.

Venturi was waiting for Tony just outside the office, grabbed him and ushered him into an unused room in the clubhouse. There the two talked as tears welled up in both their eyes and they “stumbled around the room like two blind people, trying to regain our composure,” as Tony described it. They both now knew, and felt the heartbreak, of coming so close to a Masters green jacket.

Finally, the two made their way to the presentation ceremony where they watched Palmer help Nicklaus into a size-44 regular green jacket. During the ceremony, Tony could not help but think back to that damn double-bogey on the eighth hole during Thursday’s first round. He could not help but ponder what might have been, if not for that costly mishap.

Nicklaus won a check for $20,000 while Tony had to make do with the second-place prize of $12,000. This was more money than he won in his first full year on tour, more than he won in the bleak years of 1959 and 1960 combined. The check also moved him up to third place on the official money list bumping Palmer from third to fourth.

“You’d have had champagne—the best—in the press tent, and all you could drink, if I’d have won. I would have been glad to have blown the whole $20,000 first-place money.”

Still, the check was not big enough for Tony’s tastes. He met with the press after the awards ceremony and said, “You’d have had champagne—the best—in the press tent, and all you could drink, if I’d have won. I would have been glad to have blown the whole $20,000 first-place money.”

Instead, there was only beer in the tent.

The numbness of his narrow defeat wore off and he was starting to feel philosophical, even proud of his performance. He admitted that he was “too stupid” to realize that no first-timer had ever won the Masters.

“I think I have it made,” he told reporters. “Even though I finished second, they’ve already asked me to appear on at least two television matches next year.”

“When I started out in golf as a caddy in my teens I decided I was going to adopt Walter Hagen’s philosophy of life—‘smell the roses along the way.’ Well, I’ve smelled them and I’m going to keep on smelling them.”

He pointed out to the press how valuable Ken Venturi’s help was during the tournament.

“Had I won, I would have given him half the trophy,” Tony said. “Here was a guy, who was in the field against me, yet I played four practice rounds with him, and he told me everything he knew about the course. I never would have done as well as I did had it not been for Ken. I want to pay him tribute. I have a fine family, the best. I never made college, I barely got through high school, but it wasn’t my family’s fault; they are gods to me. So is Venturi. He’s quite a guy.”

After Tony met with the press, he attended a dinner hosted by Cliff Roberts. Also present was the new champion, Nicklaus and his wife Barbara, Palmer and his wife Winnie, Gary and Vivienne Player, Billy and Shirley Casper and Charlie Coe, one of the finest amateurs in the country and a member of Augusta. Everybody toasted the winner, as well as Tony, and they enjoyed a convivial meal. The sting of defeat had worn off and Tony felt proud to finish second in such a prestigious event.

After dinner, Arnold Palmer took him aside for a man-to-man talk. He told Tony how well he played. Referring to Nicklaus, Palmer felt that Tony could “beat that kid.” He also told Tony he considered him a close friend and this particularly touched Tony. Their friendship, always warm, grew tighter after this conversation.

Larry Baush is the author of Uncorked, The Life and Times of Champagne Tony Lema available at 9acespublishing.com or on Amazon as a paperback or Kindle edition. Larry carries a single digit handicap at Rainier Golf and Country Club in Seattle, Washington. He is the editor of tourbackspin.com. You can contact larry at larry@9acespublishing.com.

© 2020 9 Aces Publishing | All Rights Reserved