“My God, I’ve Won The Open” is Part Two of a three-part article on the magical summer of 1964 for Ken Venturi and Tony Lema. Part One, The Ties That Bind documents the friendship between the two players and how a small equipment manufacturer hit the jackpot after the duo’s accomplishments during the summer of 1964. You can read Part One HERE.

by Larry Baush

Tony Lema arrived in Washington, D.C. For the U.S. Open riding a roller coaster of emotions and expectations; his confidence was soaring from two straight victories on tour, but he was also dead tired physically and mentally worn out.

“Winning three in a row is out of line with the odds,” he told reporters in a pre-tournament press gathering. “I’m tired, while the big two—Jack Nicklaus and Arnold Palmer—are fresh, with plenty of practice behind them.”

Meanwhile, Ken Venturi arrived at Congressional Country Club, site of the 64th U.S. Open, on a comeback trail that showed guts and determination. It included going through local and sectional qualifying to earn a ticket to a tournament he hadn’t qualified for in the previous three years. The comeback also featured strong finishes in the Thunderbird Classic in early June and the Buick Open the following week—the same two tournaments that Lema won.

The weather that greeted the players in D.C. that week was hot and muggy even though forecasts called for the weather to be fair and cool with temperatures in the 70s. Monday’s weather defied that forecast and the sweltering, sunny weather helped get the fairways and greens firm; just how the U.S.G.A wanted them. The course measured 7,053 yards for the Open making it the longest course to host an Open up to that point. Par for the course was 35-35—70.

Congressional is located 10 miles away from the White House as a helicopter would fly to Bethesda, Maryland but roads in 1964 made the trip considerably longer. The club featured 23 congressmen, six senators and one Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Byron White. The members spent $300,000 in course improvement to land the Open.

The massive stucco clubhouse sits atop a hill and overlooks the fairways that weave through stands of oak, cypress and spruce trees. For the Open, the course featured 2-inch Bermuda rough for the first 6-feet and 4-inch rough farther out. The greens were very firm in accordance with how the U.S.G.A. set up an Open course to make it a difficult test for the best golfers in the world.

The massive stucco clubhouse at Congressional Country Club

Lema was all the talk early in the week because of his 2-week hot streak. Even Arnold Palmer was impressed with Lema’s recent play and he took some of the credit.

“I’ll tell you why Tony is going so well: That rascal has my putter,” Palmer explained to reporters. “I gave him my putter earlier this year in Oklahoma City. He was having trouble on the greens and I said, ‘Here, try this.’ He did and he’s been going great guns ever since.”

Lema skipped the first day of practice to get some well-deserved rest even though he participated in a Sports Illustrated reception that included a clinic at Haines Point. Lema joined Sam Snead, Julius Boros, Art Wall and Billy Casper as they hit balls out into the water towards the Jefferson Memorial while Byron Nelson served as master-of-ceremony.

Venturi arrived in Bethesda on Monday and his top priority those first few days was to get himself better acquainted with the golf course. He felt that the course, with its length, was a perfect fit for his game. The length of the course would put a premium on long iron play and that was Venturi’s forte. His first big break of the week was the assignment of his caddy. In 1964 a tour pro could not bring a regular caddie to the U.S. Open. Venturi picked the name William Ward out of a hat and he just happened to pick the highest rated caddie at the club.

| He was a stronger player once he had a chip on his shoulder |

On Tuesday, President Lyndon Johnson hosted a lawn party for the favorites, notable contenders and past champions. Lema was invited while Venturi was not. Venturi used these types of snubs as motivation; he was a stronger player once he had a chip on his shoulder.

The winner’s share at the Open was $17,000 and Lema wanted to add that amount to the $28,00 he had won in the prior eight days with his back-to-back victories at the Thunderbird Classic and the Buick Open. Even so, it was Arnold Palmer and Jack Nicklaus who opened as the betting favorites at 4 – 1 odds. Lema was tied with Julius Boros at 6 – 1.

“There won’t be more than eight or 10 rounds under par all week,” said Jack Nicklaus.

Arnold Palmer showed up at the course on Wednesday and had to ask the whereabouts of his caddie. Turns out his caddie had quit; he couldn’t handle the pressure. “I’m a nervous wreck,” Palmer’s 31-year-old former caddie Eli Morrison said. Morrison was replaced by William Bryant who stood 5’ 6” and weighed 230 pounds.

“Arnie’s Army don’t bother me none,” Bryant stated. “I’ve played basketball and football in front of big crowds.”

Venturi only played 9 holes on Tuesday, and another 9 holes on Wednesday as it was too hot to play a full 18 holes. Even so, he was ready to play. Play finally began on Thursday with Lema teeing off at 9:27 playing with Sam Snead who was desperate to win a U.S. Open, the one major that eluded him. Lema’s good friend Bobby Nichols rounded out the group. Nicklaus followed at 9:52 playing with Paul Harney and Bob Charles. Arnold Palmer teed off at 12:25 alongside Doug Ford and Kel Nagle.

Ken Venturi blasts from a bunker during the 1964 U.S. Open

Due to a protracted slump during that time of his career Venturi was so far under the radar that the newspapers did not include his tee time. He played with Billy Maxwell and George Bayer. Venturi felt the Open pressure early in his round. He had always been a superb bunker player yet it took him two attempts to get out of the sand—twice on the front nine. He was able to salvage a bogey each time but still made the turn at 3 over and he had the more difficult back nine yet to play. He hung in and scrambled to a 2-over 72.

Despite a balky driver during the first seven holes, Arnold Palmer gave indications that he was going to control this tournament as he had in April at the Masters where he won by six strokes. He was the only player who managed to break par in the first round where he fashioned a 2-under 68. He missed a 7-foot putt for birdie on the final hole or his two-stroke lead would have been three. At 34-years-old, Palmer was on a quest to achieve the professional Grand Slam after winning the Masters. His 68 was an incredible round when you consider that he averaged just one birdie per round during his six practice rounds. Nicklaus played 52 holes of practice before he secured his first birdie. Palmer posted three birdies in the opening round.

After blistering the front nine with a score of 33, Lema bogeyed two of the last three holes to post a 1-over 71. Nicklaus was another stroke back, four strokes off the lead. Journeyman pro Bill Collins had a roller coaster day with five birdies and five bogeys to sit in second place, two strokes off Palmer’s lead.

Temperatures reached 90 degrees during the first round and despite a downpour just before dawn, Friday’s temperatures continued to push the mercury up topping out over the 90-degree mark. The weather wasn’t the hottest thing on Congressional that Friday; Tommy Jacobs, a 29-year-old from Bermuda Dunes, California, inserted his name into the record books with an incredible round of 64 that included six birdies and no bogeys. With a first round of 72 Jacobs sat in the lead at 136.

Tommy Jacobs plays with his three-year-old son, Michael in their hotel room after he shot a first round 64 at the U.S. Open

| “You must have been cheating.” |

Palmer, who finished an hour and half after Jacobs, was incredulous upon hearing about Jacobs score. “Did he play all the holes?” he jokingly asked reporters.

Later, in the locker room, he quipped to Jacobs, “You must have been cheating. Either that or you were playing a different course.

The record tying 64 shot by Jacobs matched the lowest round ever shot in the U.S. Open. Unknown pro Lee Mackey shot a 64 in the 1950 Open at Merion.

Palmer added a 69 to his first round 68 and was one stroke off Jacob’s lead. Bill Collins managed a 71 and sat at 141 and one stroke further back was Venturi—the first his name appeared in newspaper accounts of the tournament. Still, nobody gave him much of a chance and he continued to feed off his underdog status.

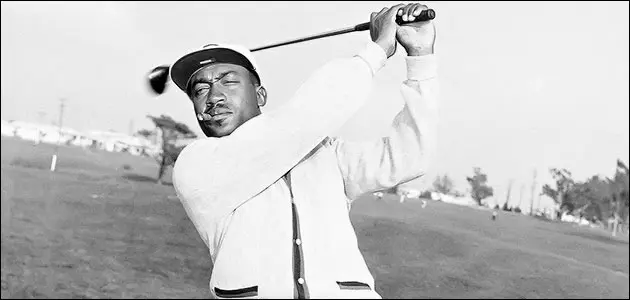

Charles Sifford, pioneering African-American player on the PGA Tour

Tied at 142 with Venturi was Charles Sifford who was described in the vernacular of the 1960s as “the husky, cigar-chomping Negro.” Lema added a 72 to his first round 71 and sat one stroke further back at seven strokes off the lead.

The grueling final 36-hole round, known as “Open Saturday” dawned with 75-degree temperatures as the first groups teed off. The course setup that greeted the players was tough; the U.S.G.A. wasn’t about to let another 64 to be posted in this tournament. They tucked pins into the most difficult positions on every hole.

On the practice putting green Lema greeted Venturi, who Lema thought looked relaxed yet focused.

“You look great today, Ken,” Lema told his long-time friend. “You know something? I have a feeling it’s going to be your day.”

“I sure hope so, Tony,” Venturi replied.

Venturi teed off and promptly birdied the first hole after he fired his approach shot to 12-feet. His birdie putt rolled up to the hole but stopped on the lip overhanging the cup. He stared at it before walking up to tap it in. As he was walking, the ball tumbled into the hole. Venturi felt it was a sign and he vowed to go for every pin. “You’ve got one stroke to play with,” he told himself. He then birdied the fourth and fifth holes. His strategy of going for the pin was paying off as he was hitting his irons close and he was making putts. The temperature was soaring and would eventually top 100 degrees with high humidity. Venturi pressed on despite the heat. He birdied the eighth hole as well as the ninth. His score for the front nine of his morning round was an unbelievable 30.

“It was the greatest nine holes I ever played,” he later said.

Venturi’s wife, Conni approached him on the tenth tee we a glass a of iced tea. Venturi want no part of it and told his wife to return to the clubhouse. The two were not getting along very well during this period and besides, he felt like a pitcher in the midst of a no-hitter and didn’t want anybody to take him out of the zone he was in. He did not drink the tea. He should have; the temperature was now over 90 degrees.

By the fourteenth hole it was apparent that there was something going wrong with Venturi.

“I started to shake all over,” he explained. “It wasn’t nerves. My whole body was shaking.” He exhibited the classic signs of dehydration.

Venturi managed to save pars at the fifteenth and sixteenth before dropping a stroke at the seventeenth, the result of 3-putt from 25-feet. On eighteen he missed a 4-foot putt. Even with the stumble at the finish he was able to post a 66 and finished the morning round two-strokes behind Tommy Jacobs and two-strokes in front of Palmer.

A station wagon drove Venturi and his playing partner, Ray Floyd, up the hill to clubhouse. Venturi was unable to eat; his face was ashen, and his eyes were glazed as he slumped with his back against his locker. He requested iced tea, lemons and salt tablets. This would be the first liquids he had all day.

| “He’s sick.” |

Tony Lema finished his morning round and came over to congratulate Venturi. He could see that something was wrong. He kept a close eye on his friend. The other pros were worried as well. Floyd went and found Conni, Venturi’s wife. “He’s sick,” he told her.

Dr. John Everett, a member at Congressional and the chairman of the Open’s medical committee examined Venturi in the locker room and his prognosis was not good; Venturi was suffering from heat prostration.

“If it were up to me, Ken,” Dr. Everett counselled. “I would take you to the hospital. You can’t go out there. It could be fatal.”

“It’s better than the way I’ve been living,” responded Venturi who was determined to complete his comeback. He pulled himself up off the floor where Dr. Everett had moved him and headed back out into the heat.

Venturi arrived at the first tee for his afternoon round and many spectators were surprised to see him. A rumor had spread that Venturi had withdrawn due to his condition. Yet, there he was. Dr. Everett accompanied him equipped with cold towels and salt tablets.

Ken Venturi tries to cool off during “Open Saturday” at Congressional Golf Club

Playing strictly on instinct, Venturi was able to par the first five holes. He dropped a shot on the sixth hole and by the time he reached the ninth tee he had learned that he was now tied with Jacobs who doubled the second hole and added a bogey as he made his way through the front nine. Game on.

The ninth hole at Congressional is a 599-yard hole dubbed The Ravine Hole as it features a deep ravine that one news columnist described as full of grass that hasn’t been trimmed since the Wilson administration. Players laid up as close to the ravine as possible for the shortest shot into the green.

Venturi laced a drive down the fairway and then almost hit his 1-iron too good; he was just yards from the edge of the ravine. Staying with his aggressive game plan he took dead aim at the back-pin location. He pulled off the shot resulting in a 9-foot birdie putt that he coaxed in the low side of the cup for another birdie. He now sat alone atop the leader board; two strokes clear of Jacobs who took another bogey.

After making a scrambling par on the tenth hole, he followed up with routine pars on 11 and 12. He was in a zone, playing on instinct. When he would ask his caddie for a yardage, the reply was always, “You don’t need the yardage, Mr. Ken; you’re at the exact same yardage you were this morning.” In fact, Venturi used the exact same club for his approach shots in the afternoon round that he did in the morning round 14 times.

Venturi played the 13th hole flawlessly resulting in a birdie and felt that the only player who could beat him now was himself. He moved slower and slower as his body reacted to the heat and he tried to fight off the effects of dehydration.

He finally arrived at the final tee. He had purposely avoided the leader boards around the course but at 18 he wanted to know where he stood. He asked Bill Hoellie, a good friend from San Francisco, where he stood. “Just stay on your feet,” his friend replied. “We’ve got it.”

Making sure to avoid hitting his approach shot left and into the water, he blocked it to the right, and it took a bad bounce into the greenside bunker. He started his walk to the green and took off his white linen cap. The applause was thunderous.

“Hold your head high, Ken,” Joesph Dey of the U.S.G.A. told him. “Like the champion you are.”

Venturi exploded out of the sand to about 10 feet from the cup and then drained the putt. He dropped his putter and then the weight of the moment hit him.

“My God, I’ve won the Open,” he quietly said to himself. Yet he remained remarkably composed—until Ray Floyd approached him. Floyd had retrieved the ball from the cup for Venturi after his birdie putt. Venturi noticed as Floyd got closer that Floyd had tears in eyes reacting to the emotional round he had just witnessed. That’s when Venturi lost it and the two men stood on the final green of the U.S. Open weeping together. Venturi became the first person in the 20th Century to win the U.S. Open after going through both local and sectional qualifying (Orville Moody accomplished the same feat in 1969).

Lema shot 75-75 on Open Saturday and finished in 20th place. After he finished and cleaned out his locker, he placed a phone call to the operator at the hotel where Venturi was staying. He requested that he be the first call put through to his friend’s room when he arrived after his post round interviews. The operator accommodated his request and he was the first person to talk to Venturi once had departed the grounds at Congressional.

“Congratulations,” Lema said. “I knew you could do it.”

Next Post: Part Three of the magical summer of 1964 | The Open Championship at The Old Course in St. Andrews

Larry Baush is the author of Uncorked, The Life and Times of Champagne Tony Lema available at 9acespublishing.com or on Amazon as a paperback or Kindle edition. Larry carries a single digit handicap at Rainier Golf and Country Club in Seattle, Washington. He is the editor of tourbackspin.com. You can contact larry at larry@9acespublishing.com.